Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.

~Thomas Merton

| |||||||||

| Shhh...I took a picture of Maddie and John Schoenherr's Sandworms of Dune, 1977 |

Our first adventure for the 2013 summer Camp Mommy

extravaganza is our local museum. Our museum does its best to get the best

exhibits it can and over the last few years has exceeded expectations. Last year Maddie and I spent our time viewing

some of the most incredible science fiction/fantasy paintings ever created. Included in the exhibit were images and

sculptures by H.R. Geiger, one of the paintings upon which the original cover

of Dune was based, at least five

Tolkien inspired works, and many Boris Viejo pieces. There was concept art, costumes, and other

tremendously large sculptures. Some of them were so life-like I had to stop

Maddie (and myself) from touching (and

I’ll tell you a little secret..I snapped a few pictures. Shhhhh). Though not a part of the science

fiction exhibit, the Allentown Art Museum also had a Victorian Mourning exhibit

around that time. Though small in size,

the pieces included historic mourning garb, mourning jewelry, hair art, and

modern jewelry interpretations of Victorian mourning culture.

This summer The Allentown Art Museum is hosting a collection

of the works of Henri

de Toulouse-Lautrec. Not only is this

Maddie’s first exposure to the historic fine art of Europe, it’s one of mine as

well. I’m glad her first exposure is so early and a painter I love and

understand and can translate to Maddie. The

only other major art exhibit I ever saw was Marcel Duchamp when I was about 5 or

6. I had no idea why there was a toilet

inside a museum, and I couldn’t figure out how a big piece of broken glass with

bunch of triangles, circles, and lines could be a bride (and I had no idea what bachelors were and why they were making her naked). I kind of still don’t…and I took a fine arts

class in college.

My step-father was an artist who, unfortunately, never

took the time to explain to me the art he loved, or help me appreciate what

I saw. Perhaps I would have loved Duchamp. All these years later I believe he

felt one should simply instinctively

understand and be Zen about viewing a piece of art, and while I agree with that

fundamentally and am a firm believer that the first emotion you feel in regard

to any piece of art is the one you take with you forever, I also believe

guidance is necessary, especially for a small child. Duchamp confused and frustrated me, and

though I have learned about him since, and come to appreciate his talent and

vision, I will never truly love him, taking those initial feelings of

frustration with me as well as the internal “ugh” I hear myself say when

someone mentions him. Had my step-father taken the time to crouch down next to

me and explain the toilet in the museum (or simply the vision of the

conceptual/Dadaism movements) I might have had a very different first experience.

So

what does Duchamp mean to me all these years later? What does it mean for my daughter? I think my

younger child’s first exposure to art should be something I can explain. I

don’t mean interpret, as that is up

to the individual and you must

encourage that, but give background information on, and help her understand

the vision behind the piece itself.

Either that, or find artwork that we can learn about together. I have a passion for the Belle Époque and the Fin de siècle so this Toulouse-Lautrec exhibit has me giddy with excitement. I took a book on Toulouse-Lautrec out from the library and we sat together and looked at his paintings. She saw a picture of him and asked about his legs. When I told her what happened to him she said, "well, I guess it didn't hurt his painting." Even there we see a lesson in tolerance and understanding.

You have one activity to do before you go to the museum. You have to give your child a basic understanding of the idea of different styles. Several years ago my boyfriend's son came home with a project he did in art class. Most schools are doing away with art classes unfortunately, so it falls to you to teach appreciation. Below is a copy of his project. The best way to do this is to choose eight different painters. Fold a regular piece of unlined drawing paper so you have eight boxes. Put the name of one painter in each box. Show your child one piece of work by that painter, discuss what it looks like, and have your child do a small scale, simple reproduction. If you discuss Jackson Pollack, have your child use markers of many colors and draw dots all over the inside of the box. Below is a list of 10 artists and one piece of representative art. You can look up all these pieces on the internet. Don't worry if your child can't draw a real person if you talk about Rafael...stick figures with wings works!

Definitions of Artistic Movements

Impressionism: 19th century art movement centralized in Paris. Characteristics include relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles.

Post-impressionism: Originated in the early 20th century. Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations: they continued using vivid colours, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, but they were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, to distort form for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary colour.

Pre-Rafaelite: Middle to late 19th century British movement that rejected the mechanical religious works of the Renaissance. These painters returned to the subjects of myth and legend, and rejected art that was seemingly done by rote and convention.

Dadaism: (Ahhh! Marcel Duchamp!) An artistic moment in the early 20th century that valued nihilism, nonsense, and travesty. It rejected conventional art.

Cubism: A movement of art that originated in 1907 and is still practiced today. Cubism has several key components: geometricity, a simplication of figures and objects into geometrical components and planes that may or may not add up to the whole figure or object known in the natural world, conceptual reality instead of perceptional reality, distortion of reality, the overlapping of planes, multiple views of the subject matter. Seems like a difficult concept, but when you view a Picasso, you'll get it.

Futurism: From Italy around the same time Cubism was developing. A style of art that embraced mechanism and industrialsim.

Surrealism: Also an early 20th century movement. Surrealism valued the insights and subconscious realities highlighted by Freud. It included ideas of strong emotions, emotional repression, mystical ideas, ambiguity, and the ideas of chance and spontaneity.

Contemporary: Art from the 1960's or 70's up until this very minute. Contemporary art can involve all previous art styles and most often addresses contemporary issues such as AIDS, poverty, multiculturalism, globalization, and gender issues. Contemporary art has often been attacked as pointless scribbles that could have been made by someone's 3 year olds; however, this is not the case. This kind of art is planned and constructed with vision and the desire to share feelings, images, and ideas just like any other piece of art.

10 Artists and Their Most Famous Works (my opinion anyway!)

Should I go into "why art is important" or do you know that already? I think you know that already. If you believe art is important you must do what you can to make it interesting and fun. You must do what you can to prevent the eye rolls and sighs when your child has a school trip or is going with you to the museum. The only way to achieve this is to be excited right along with them, even if you don't like the museum very much yourself. There are a lot of questions you can ask your child while viewing paintings or sculptures that will increase your child's interaction and instinctual understanding of art. It might help you as well. There is nothing more wasteful than going to a museum, viewing works of art, and leaving with no more enlightenment within you than there was when you walked in. The only way to combat that is to TALK about what you see (quietly of course...proper manners in museums is another important lesson). Talk, talk, talk. Talk at the museum, talk on the way home, talk when you get home.

You have one activity to do before you go to the museum. You have to give your child a basic understanding of the idea of different styles. Several years ago my boyfriend's son came home with a project he did in art class. Most schools are doing away with art classes unfortunately, so it falls to you to teach appreciation. Below is a copy of his project. The best way to do this is to choose eight different painters. Fold a regular piece of unlined drawing paper so you have eight boxes. Put the name of one painter in each box. Show your child one piece of work by that painter, discuss what it looks like, and have your child do a small scale, simple reproduction. If you discuss Jackson Pollack, have your child use markers of many colors and draw dots all over the inside of the box. Below is a list of 10 artists and one piece of representative art. You can look up all these pieces on the internet. Don't worry if your child can't draw a real person if you talk about Rafael...stick figures with wings works!

|

| Aidan B. School art project (about 2010 or so) |

Definitions of Artistic Movements

The best online dictionary of artistic movements is found at Art History on About.com. Most of the definitions here are amalgamates of Art.com and Wiki entries.

Impressionism: 19th century art movement centralized in Paris. Characteristics include relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles.

Post-impressionism: Originated in the early 20th century. Post-Impressionists extended Impressionism while rejecting its limitations: they continued using vivid colours, thick application of paint, distinctive brush strokes, and real-life subject matter, but they were more inclined to emphasize geometric forms, to distort form for expressive effect, and to use unnatural or arbitrary colour.

Pre-Rafaelite: Middle to late 19th century British movement that rejected the mechanical religious works of the Renaissance. These painters returned to the subjects of myth and legend, and rejected art that was seemingly done by rote and convention.

Dadaism: (Ahhh! Marcel Duchamp!) An artistic moment in the early 20th century that valued nihilism, nonsense, and travesty. It rejected conventional art.

Cubism: A movement of art that originated in 1907 and is still practiced today. Cubism has several key components: geometricity, a simplication of figures and objects into geometrical components and planes that may or may not add up to the whole figure or object known in the natural world, conceptual reality instead of perceptional reality, distortion of reality, the overlapping of planes, multiple views of the subject matter. Seems like a difficult concept, but when you view a Picasso, you'll get it.

Futurism: From Italy around the same time Cubism was developing. A style of art that embraced mechanism and industrialsim.

Surrealism: Also an early 20th century movement. Surrealism valued the insights and subconscious realities highlighted by Freud. It included ideas of strong emotions, emotional repression, mystical ideas, ambiguity, and the ideas of chance and spontaneity.

Contemporary: Art from the 1960's or 70's up until this very minute. Contemporary art can involve all previous art styles and most often addresses contemporary issues such as AIDS, poverty, multiculturalism, globalization, and gender issues. Contemporary art has often been attacked as pointless scribbles that could have been made by someone's 3 year olds; however, this is not the case. This kind of art is planned and constructed with vision and the desire to share feelings, images, and ideas just like any other piece of art.

10 Artists and Their Most Famous Works (my opinion anyway!)

|

| Mona Lisa, Leonardo da Vinci, 1509 (Renaissance) |

| ||

| Starry Night, Vincent Van Gogh, 1889 (Post-impressionism) |

| |

| Number 8, Jackson Pollack, 1949 (Abstract Impressionsim) |

|

| The Scream, Edvard Munch, 1893 (Expressionist) |

|

| Water Lilies Clouds, Claude Monet, one of 250 Water Lily paintings (Impressionsim) |

|

| The Persistence of Memory, Salvador Dali, 1931 (Surrealism) |

|

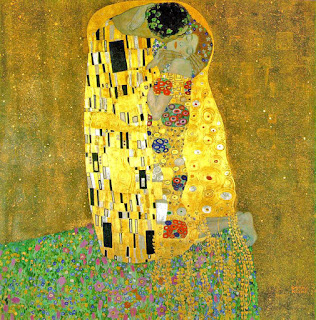

| The Kiss, Gustav Klimt, 1908 (Symbolist) |

| |

| Two Dancers On the Stage, Edgar Degas, 1874 (Impressionism and Realism) |

.jpg) | |

| Girl With a Pearl Earring, Jan Vermeer, 1665 (Baroque) |

|

| Woman in a Hat with Pompoms and a Printed Shirt, Pablo Picasso, 1962 (Cubism) |

Should I go into "why art is important" or do you know that already? I think you know that already. If you believe art is important you must do what you can to make it interesting and fun. You must do what you can to prevent the eye rolls and sighs when your child has a school trip or is going with you to the museum. The only way to achieve this is to be excited right along with them, even if you don't like the museum very much yourself. There are a lot of questions you can ask your child while viewing paintings or sculptures that will increase your child's interaction and instinctual understanding of art. It might help you as well. There is nothing more wasteful than going to a museum, viewing works of art, and leaving with no more enlightenment within you than there was when you walked in. The only way to combat that is to TALK about what you see (quietly of course...proper manners in museums is another important lesson). Talk, talk, talk. Talk at the museum, talk on the way home, talk when you get home.

Ten Questions to Ask Your Kids About Art

(courtesy of Project Muse)

1. Look carefully at the work of art in front of you. What colors do you see in it? Take turns listing the specific colors that y ou see (for example: "I see red." "I see purple.")

2. What do you see in the work of art in front of you? Take turns listing the objects that

you see (for example: "I see an apple." "I see a triangle.")

3. What is going on in this work of art? Take turns mentioning whatever you see happening, no matter how small.

4. Does anything you have noticed in this work of art so far (for example: colors, objects, or events) remind you of something in your own life? Take turns answering.

5. Is this work of art true to life? Ho w real has the artist made things look?

6. What ideas and emotions do you think this work of art expresses?

7. Do you have a sense of how the artist mi ght have felt when he or she made this work of art? Does it make you feel one way or another?

8. Take a look at the other works of art displayed around this one. Do they look alike? What is similar about the way they look (for example: objects,events, feelings, the way they are made)?

What is different?

9. What would you have called this work of art if you had made it yourself? Does the title of the work, if there is one, make sense to you?

10. Think back on your previous observations. What have you discovered from looking at this work of art? Have you learned anything about yourself or others? Now that the game is over, ask your kids again: Do you like this work of art? Why or why not? Has your reaction to the work changed? Do you like it more or less than you did in the beginning? Why?